China is renowned for its remarkable linguistic diversity. Within its borders, people speak hundreds of different languages and dialects belonging to several language families. At the same time, Mandarin Chinese (Putonghua) – based on the Beijing dialect – serves as the official national language and a lingua franca across regions. This dual reality means that while most Chinese citizens can communicate in Mandarin, they often grow up speaking a regional dialect or even a completely different language at home. According to recent surveys, over 80% of China’s population can speak Mandarin (up from about 70% a decade prior), yet Ethnologue estimates 298 distinct languages are still spoken in China, spanning more than 9 different language families. In other words, one national language links the country, but numerous local languages and dialects continue to thrive in various regions.

In this report, we will explore the diversity of language use across China’s regions. First, we examine how Mandarin pronunciation varies by region – essentially “one language, different pronunciations.” Next, we look at China’s major regional dialects and minority languages, and how they are distributed geographically. We then discuss trends in language use, including the decline or preservation of dialects amid the spread of Mandarin, as well as generational shifts in attitudes. Finally, we consider the landscape of foreign language proficiency in China – such as English, Japanese, and Russian – and how such skills vary across different areas. Throughout, we will incorporate the most recent data from credible sources to provide an up-to-date, balanced overview. Let’s begin with the many flavors of Mandarin itself.

Mandarin Chinese may be the “common language” of China, but its pronunciation varies noticeably across regions. Standard Mandarin (Putonghua) is modeled on the Beijing dialect’s pronunciation, yet in practice few people speak perfect textbook Mandarin in daily life. Instead, most Mandarin speakers infuse their local accent or topolect into their speech. For example, many people in northern China (especially Beijing) use a distinctive “er” sound at the end of words (a feature called erhua, 儿化音) , giving their Mandarin a recognizable Beijing flavor. By contrast, in southern Mandarin-speaking regions, speakers often do not distinguish the retroflex consonants. Sounds like “zh, ch, sh” tend to be pronounced more like “z, c, s,” making words such as shí (stone) and sí sound similar. Likewise, some southerners merge the sounds “n” and “l” (e.g. saying la for na) , or even mix up “h” and “f” in certain words . These accent variations mean that someone from, say, Guangdong or Sichuan might speak Mandarin quite differently from someone in Beijing or Harbin. Yet despite the regional quirks, Chinese people generally understand each other’s Mandarin, and these differences are often regarded with pride or humor rather than as barriers.

It’s worth noting that Mandarin itself has multiple regional sub-variants. Linguists often divide Mandarin into subsets like Northeastern, Northern, Southwestern, etc., which have slight differences in tones and vocabulary. For instance, the Southwestern Mandarin spoken in Sichuan and neighboring areas has a sing-song intonation and some colloquial words unfamiliar to Beijingers. Taiwan’s version of Mandarin (while outside mainland China) also has a softer accent and different word choices compared to Putonghua. Despite these nuances, all these variants are considered forms of Mandarin Chinese. Through national education and media (all broadcasts are in standardized Mandarin), most people can adjust their speech towards the standard when needed. At the same time, local accents remain a source of identity. Someone’s Mandarin pronunciation can often give away their hometown, and accents are fondly parodied in comedies and social media. In short, one language, many accents is an everyday reality – a Shanghainese, a Beijinger, and a Cantonese may all chat in Mandarin, but each with a distinct twang.

A linguistic map of China showing the predominant languages/dialects in different regions (Mandarin-speaking areas in light aqua, Wu Chinese in purple, Yue/Cantonese in green, Min in blue, etc.).

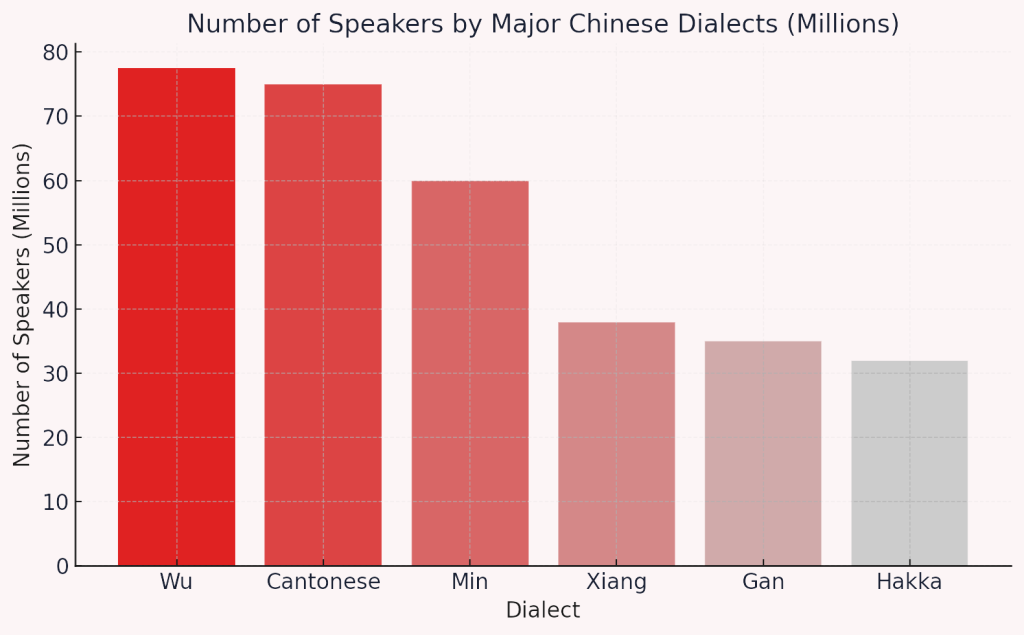

China’s Han majority speaks a variety of Chinese dialect groups, which are often so divergent that they are mutually unintelligible. These are sometimes called “dialects” in a cultural sense, but from a linguistic perspective many are distinct languages within the Chinese language family. The seven major Chinese dialect families are typically listed as: Mandarin, Wu, Yue, Min, Xiang, Gan, and Hakka. Mandarin (in a broad sense) is the largest, native to northern and southwestern China, and as noted comprises about 70–73% of China’s population as a first language. The other groups are spoken in specific regions: for example, Wu Chinese (which includes Shanghainese and Suzhou dialect, among others) is spoken in Shanghai, southern Jiangsu, and Zhejiang, with roughly 75–80 million native speakers. Yue Chinese, better known as Cantonese, dominates in Guangdong, Guangxi and Hong Kong, and has around 70–80 million speakers. Min Chinese (including Hokkien, Teochew, etc.) is spoken in Fujian, eastern Guangdong (Chaozhou/Shantou), Hainan and Taiwan, also accounting for tens of millions of speakers. Other groups like Xiang (Hunan province), Gan (Jiangxi province), and Hakka (scattered in Guangdong, Fujian, etc.) each have on the order of <50 million speakers and are largely confined to those regions. These languages share a common written form (Chinese characters) but are phonetically very different– a person from Shandong and a person from Guangzhou reading the same Chinese text aloud would sound completely different, yet they could communicate through writing. Such is the unique diglossic situation in China: a unified written language alongside diverse spoken tongues.

In addition to the Han Chinese dialects, China is also home to a rich array of minority languages. About 8% of China’s population belong to 55 officially recognized ethnic minority groups, many of whom have their own languages. These languages span several language families (such as Turkic, Mongolic, Tibeto-Burman, etc.). For example, in the western region of Xinjiang, millions speak Uyghur (a Turkic language written in Arabic script), and Kazakh. In Tibet and parts of Sichuan/Yunnan, the Tibetan language (of the Tibeto-Burman family) is predominant. In Inner Mongolia, Mongolian (Altaic family) is a regional official language and is written in traditional Mongolian script. Other notable minority languages include Zhuang (Tai-Kadai family, spoken in Guangxi), Korean (spoken by ethnic Koreans in northeast China), Miao (Hmong), Yi, Hui (many Hui use Chinese but some know Arabic for religious purposes), Kazakh, Dong, and many more. In fact, there are approximately 300 minority languages in China (many with relatively small speaker populations). The Chinese government grants certain minority languages official status in their regions – for instance, Mongolian in Inner Mongolia, Tibetan in Tibet, Uyghur in Xinjiang, and Korean in the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture. These languages are used in local education, signage, and media alongside Mandarin. However, much like the Han dialects, some minority languages are under pressure from the dominant Mandarin. Younger generations of minority communities often grow up bilingual in Mandarin and their native tongue, with varying degrees of fluency.

Notably, the usage of regional dialects (both Han Chinese and minority languages) has been shifting in recent years. We will examine these sociolinguistic trends in the next section – looking at how Mandarin’s spread is affecting dialect use, and the efforts to preserve linguistic heritage in the face of national language homogenization.

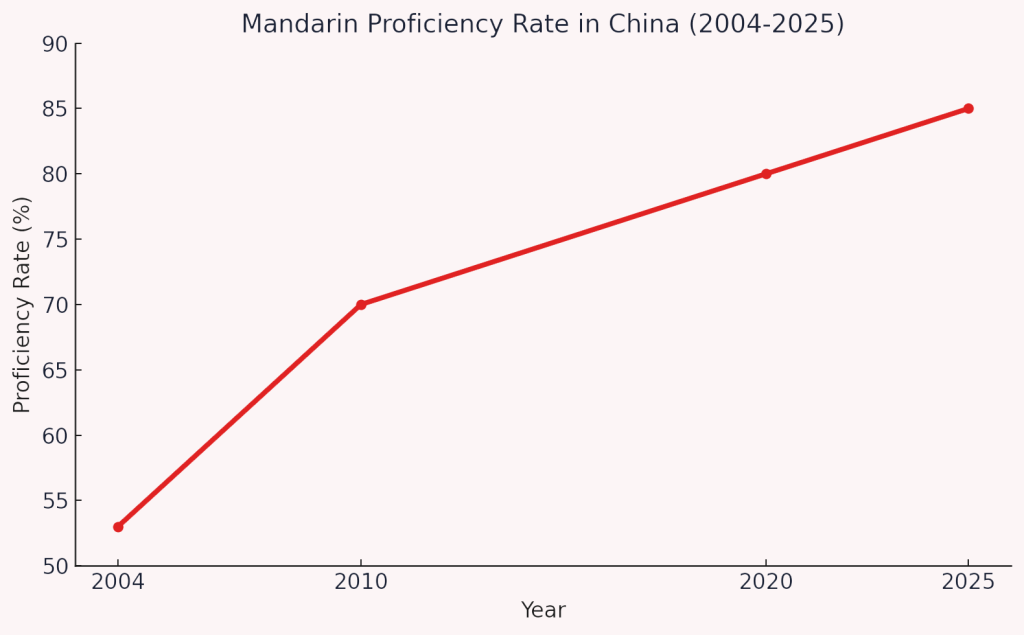

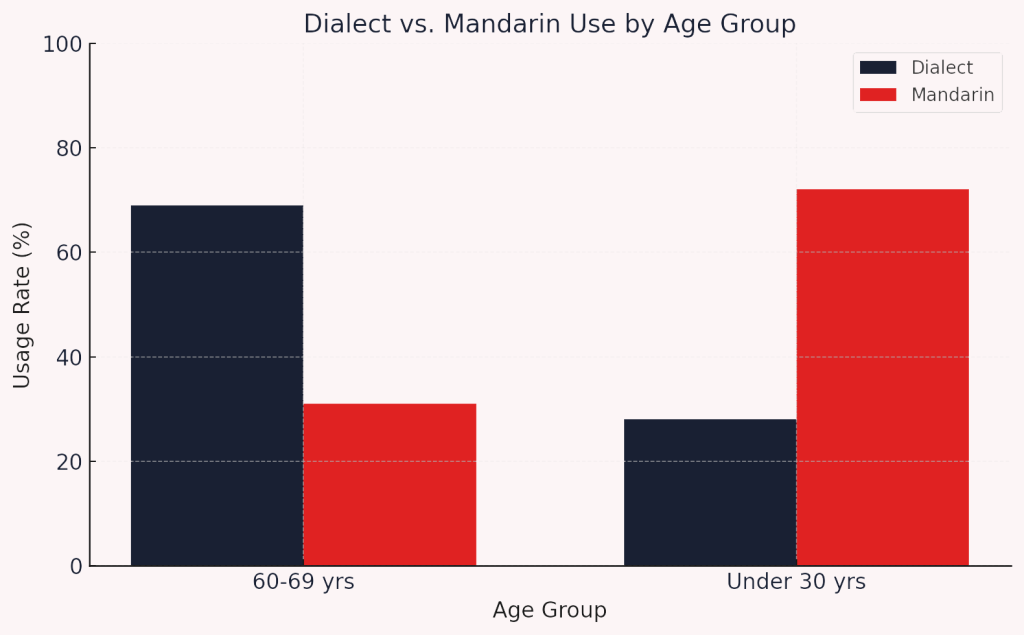

Over the past few decades, China has seen a clear shift toward increased use of Mandarin in daily life – especially among the younger generation – often at the expense of local dialects. Thanks to universal education in Putonghua and mass media, fluency in standard Mandarin has surged. In 2004, only about 53% of Chinese citizens could communicate in Mandarin; by 2020, that figure exceeded 80%. The government has actively promoted Mandarin as a national lingua franca. In 2021, a State Council plan set a goal for 85% of the population to speak Mandarin by 2025. This campaign has been highly successful among youth: a study in Beijing found that nearly half of local residents born after 1980 prefer using Mandarin over the Beijing dialect. Similarly, nationwide surveys show that while older generations may still primarily use dialects, younger Chinese overwhelmingly speak Mandarin (often as their dominant or even sole tongue). For example, in one survey only 31% of people aged 60–69 could speak Mandarin, versus more than double that percentage among those under 30. This generational language shift is evident in many families: grandparents might converse in the regional dialect, while children reply in Mandarin.

Consequently, many regional dialects are in decline, especially in urban areas. Linguists have raised alarms that younger Chinese in some dialect communities cannot fluently speak their ancestral tongue. A 2017 survey (circulated online) noted that among China’s ten major dialect groups, Wu Chinese (e.g. Shanghainese) had the fewest active speakers aged 6–20. In other words, many children in the Wu-speaking region (eastern China) are not learning to speak Wu dialects natively. Similar concerns exist for dialects like Cantonese in Guangzhou, Hakka in Guangdong, and Min in parts of Fujian, where Mandarin is becoming the default for the young. Even in Beijing, the local Beijing dialect is fading — many young Beijingers today speak a “neutral” Mandarin and cannot fully understand the old Beijing dialect rich in colloquialisms. Scholars describe this phenomenon as language diglossia, where Mandarin is used for public and formal communication, and local dialects (if spoken at all) are confined to family or informal settings. In 2004, for instance, only 18% of people reported speaking Mandarin at home with family, whereas dialect remained the home language for most, even though Mandarin was used by 42% at work or school. But as older speakers pass on and younger ones stick to Mandarin, home use of many dialects has diminished.

These trends have prompted efforts to preserve local languages and dialects. In communities where dialects are threatened, cultural activists and local governments have taken steps to document and promote them. For example, in Shanghai there have been campaigns to encourage speaking Shanghainese: locals have created Shanghainese video content, and volunteers even produced an audio recording of an entire novel in Shanghainese to share online . In 2020, a Shanghai municipal representative called for more support for the dialect, leading to the expansion of a local Shanghainese opera festival as a preservation initiative. Guangzhou has dialect programs on radio, and some schools in Chaoshan (eastern Guangdong) have experimented with Teochew (a Min dialect) classes to keep the language alive. The government’s stance is somewhat complex: while it strongly promotes Putonghua for national unity, it also officially acknowledges the cultural value of dialects and minority languages. Policy documents have stressed protecting the linguistic heritage of ethnic minorities and even local dialect culture. In practice, however, there are regulations that limit dialect usage in certain domains (for instance, a ban on using local dialects by officials in some workplaces, as occurred in Sichuan in 2020, or rules discouraging dialect broadcasts on national TV. This has led to debate: some see the diminishing of dialects as the price of forging a common identity, while others worry about the loss of cultural richness. A positive side effect noted by some sociologists is that greater Mandarin use can reduce language barriers between Chinese from different regions – today, a newcomer in Shanghai who only speaks Mandarin won’t face the social exclusion that migrants might have experienced decades ago for not knowing the local dialect. Balancing linguistic diversity with national cohesion remains an ongoing challenge for China.

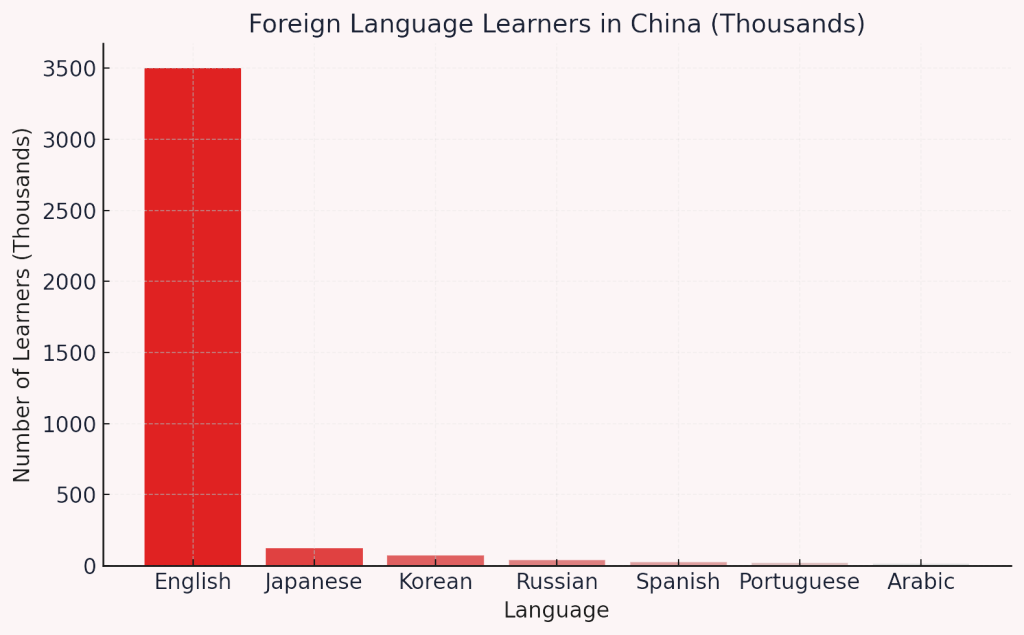

Besides the vast internal diversity of Chinese languages, China also has a complex relationship with foreign languages. English in particular has become the primary foreign language taught nationwide. Since the economic reforms, English education has been mandatory in schools (typically starting by 3rd grade of primary school) , and today the majority of students learn English as a required subject. In fact, over 93% of Chinese who study a foreign language choose English. This has resulted in an enormous number of English learners – by some estimates, around 300–400 million Chinese are learning English at any given time. However, there is a stark contrast between the number of learners and actual proficiency levels. Various studies indicate that only a relatively small fraction of the population can use English comfortably. According to a national survey, roughly 3.5% of people in Mainland China can speak English at a conversationally fluent level (equivalent to B2 level in CEFR). More advanced fluency (C1 level or above) is rarer, self-reported by about 1.8% of the population. In absolute terms, it’s estimated that about 10–25 million Chinese people are proficient in English – a sizable number, but still only a small percentage of China’s 1.4 billion people. The average English skill level in China is considered low by global standards; for example, the EF English Proficiency Index (2023 edition) ranks Mainland China only #82 out of 113 countries (with a “low proficiency” score) .

English proficiency in China varies widely by region and city. Generally, major urban and coastal areas boast far better English skills than rural inland regions. In big cosmopolitan cities, a noticeable segment of the population speaks English. For instance, in Shanghai and Beijing, roughly 10% or more of residents can speak English with moderate fluency. Surveys show about 12% of Shanghainese and 9% of Beijingers are comfortable conducting a conversation in English (B2 level or above), compared to only a few percent in less developed provinces. Correspondingly, Shanghai and Beijing score in the “moderate proficiency” band on EF’s index (with scores around 510), whereas central and western provinces like Henan or Hunan score much lower (in the 420–440 range, “very low” proficiency). According to EF’s 2023 regional breakdown, coastal Zhejiang province achieved one of the top English scores (EF EPI score 502), while landlocked Ningxia scored only 434. This reflects disparities in education quality, economic exposure, and international interactions. Cities such as Guangzhou and Shenzhen (in Guangdong) also have relatively high English familiarity given their trade and foreign investment, whereas more remote areas (say, rural western China) see far less English use.

Apart from English, the other foreign languages learned and spoken in China show interesting patterns often tied to regional and historical factors. Japanese has long been the second most popular foreign language to study (after English). Following closer Sino-Japanese ties in the late 20th century, Japanese became a common second language in universities. As of a recent survey, over 1 million people in China were learning Japanese (the highest number of Japanese learners in any country) () (). Interest in Japanese is particularly strong in some coastal provinces – for example, Guangdong, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang have seen increases in Japanese language enrollment in high schools (). Korean is another language with a substantial following, especially in the Northeast (due to the ethnic Korean population in Jilin and Liaoning) and among young fans of Korean pop culture nationwide. Russian occupied an important place in the 1950s–60s (when it was taught as the primary foreign language), and today it remains in the curriculum of some northern universities. In Northeast China, there are even bilingual schools offering Mandarin-Russian or Mandarin-Korean instruction. The Russian language is still taught in Heilongjiang and other areas bordering Russia, though English has largely replaced it as the dominant foreign language since the late 1970s. Other European languages like French, German, Spanish, and Portuguese are also taught, but usually on a smaller scale or at specialized universities. Notably, there has been growing interest in Spanish and Portuguese in the 2010s, partly due to China’s expanding trade and investment in Latin America and Africa. Likewise, more students have begun studying Arabic in recent years, some motivated by cultural interest or job opportunities in the Middle East (Arabic study is also common among the Hui Muslim community). Overall, while English remains by far the most widespread foreign language in China, each region may have its own foreign language trends – a legacy of geography, ethnic ties, and global economic links.

It is also interesting to see how foreign language proficiency correlates with demographics. Generally, younger, urban, and more educated Chinese are the most likely to speak a foreign language (especially English). For example, college graduates in big cities often have at least a basic command of English. In 2022, about 1 in 3 Chinese university students were enrolled in an English language course. Exposure to the internet and global media has further boosted English familiarity among urban youth. That said, foreign language use in daily life remains limited for most people unless their job or environment requires it. A 2006 survey found that even in Beijing and Shanghai, only about 15–16% of residents reported using English regularly in their daily lives (a rate about twice the national average. This indicates that while many have learned some English, regular usage is concentrated in certain professions (like tourism, foreign trade, higher education) and in international metropolitan settings.

In summary, foreign language proficiency in China remains uneven. English is nearly ubiquitous in the education system, yet truly fluent speakers are relatively few, and they are predominantly in the more developed coastal cities. Other foreign languages occupy smaller niches, often tied to local interests (Japanese in business and pop culture, Russian in the northern border regions, etc.). As China continues to internationalize, foreign language skills – especially English – are highly valued and are likely to improve over time, but for now the country as a whole still lags behind many smaller nations in this area. The linguistic landscape of China thus spans not only the rich tapestry of internal languages and dialects, but also an evolving engagement with external languages of the world.

China’s linguistic landscape is extraordinarily diverse and dynamic. On one hand, Standard Mandarin now provides a common communicative bridge across this vast nation, with ever-increasing adoption even in remote corners. Government initiatives aim to further solidify Mandarin’s role so that almost the entire population can speak it by 2035 . This helps facilitate mobility, education, and national cohesion. On the other hand, regional languages and dialects contribute immensely to China’s cultural heritage and local identities. The variations in speech – from the lilting Cantonese of Guangzhou to the earthy Sichuan dialect of Chengdu to the chorus of minority languages in the West – add color and character to the country’s social fabric. There is an ongoing balancing act between promoting a unified national language and preserving linguistic diversity. In recent years, policymakers have recognized this: a national language conference in 2021 emphasized both the spread of Putonghua and the protection of minority languages and dialect resources. Indeed, China is investing in documentation projects (for example, compiling dialect dictionaries and recording oral histories) to ensure these languages are not lost.

Looking ahead, the linguistic diversity across China’s regions will continue to evolve. Mandarin’s prevalence will likely keep growing, especially as younger, more mobile generations favor it. At the same time, there is increased awareness of the value of bilingualism and multilingualism. A Chinese child in 2025 might grow up speaking Mandarin at school, a local dialect with grandparents, and learning English (or another foreign language) for future opportunities – a linguistic repertoire far broader than that of previous generations. Such realities make China a fascinating case of language coexistence: one country, many tongues. By valuing this diversity while also nurturing shared means of communication, China’s many regions can maintain their unique linguistic heritage within a unified national tapestry.

You Might Also Like: What Are the Most Spoken Languages in Asia?